Back to The Girl with No Name

Forward by Master-Historian Maritza Ortskt-Dukovna

Every

country has its legends; the stories of people whose lives have

transcended historical reality into that strange space between truth and

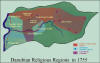

fantasy. The Grand Duchy of Upper Danubia (or the Danubian Republic, as

we prefer to call ourselves today) is certainly no exception to that

common trend throughout humanity. In our case we have the stories of the

Ancients, the Byzantine Priests who converted us, the exploits of King

Vladik the Defender and his son-in-law, and songs about the Nymphs who

defended the Duchy when almost all of its men had been killed.

Every

country has its legends; the stories of people whose lives have

transcended historical reality into that strange space between truth and

fantasy. The Grand Duchy of Upper Danubia (or the Danubian Republic, as

we prefer to call ourselves today) is certainly no exception to that

common trend throughout humanity. In our case we have the stories of the

Ancients, the Byzantine Priests who converted us, the exploits of King

Vladik the Defender and his son-in-law, and songs about the Nymphs who

defended the Duchy when almost all of its men had been killed.

However, Danubia's favorite story has always been the saga of "Bezimyackta",

commonly translated into English as "the

Girl-with-No-Name". "Bezimyackta" shows up in historical records starting around

1750, and seems to have completely disappeared around ten years later.

According to witnesses who claimed to have seen her, she was the

prettiest, smartest, and nicest young woman imaginable. However, she was

condemned to always be on the run, tormented by the Destroyer who

followed closely behind her. In earlier versions of the story, the

Destroyer, who at the time still was identified with the Christian

Beelzebub, had a semi-human form and rode on her shoulder. Later, the

story goes that she was running from the Destroyer. Because the

Destroyer could never quite catch her, the Destroyer's vengeance was

inflicted on anyone the Girl-with-No-Name tried to love.

Bezimyackta's adventures began at her home in Rika Heckt-nemat.

The legend claims that she was so beautiful that the town's other women

couldn't bear to look at her, and demanded that the council's elders

order her executed. Bezimyackta made a pact with the Destroyer

to escape, and as soon as she was gone, the Destroyer condemned everyone

in the town to die from the plague. Bezimyackta ran from

province to province, trying to find love, protection, and peace. Many

men loved her, and all of them died tragically. When the

Girl-with-No-Name fled to Danubikt Moskt and the Grand Duke fell in love

with her, to punish the Duke, the Destroyer burnt the entire capitol.

In the end, no one knew what became of the "Girl-with-No-Name". For a

decade she wreaked havoc on the people who crossed her path and then

vanished without a trace. She became the favorite subject of campfire

songs and a story to scare children, especially boys and teenagers. I

think every mother in Danubia is guilty of telling her sons to avoid

strange women who seem too beautiful to be true, especially ones in the

woods or on the roads, because somewhere Bezimyackta continues

her tormented voyage.

In 1855, on the 100th anniversary of the Great Fire that destroyed the

nation's capital, the famous Danubian poet and song-writer Danguckt Tok

compiled the stories of Bezimyackta into a song, which,

although over-simplified, continues to be the best-known version of the

legend.

The girl condemned to wander

The anguish in her soul

Her Path in Life is destruction

The darkness rides her shoulder

In her eyes there's nothing but pain

She will reach out to you

Yes, you're the one who'll save her

But take her hand

and her kiss will seal your fate

The Destroyer holds out his bait

and for you, oblivion awaits

One important job of the historian is to attempt to reconstruct the

events that inspired a legend. Many historians will reject a legend on

impulse, only to later discover archeological or documentary evidence

that does indeed offer proof that events described in the story actually

did happen. I take a different approach, because I believe that most

legends are embellished truth, not pure fantasy. Those stories exist for

a reason: they were based on something that at one time was factual.

Therefore, we must start our investigation by taking these ancient

stories at face value and only dismiss details as we find direct

evidence that discredits them. Even when events turn out to not have

taken place as described by the chroniclers, we can use other research

to reconstruct what actually did happen and often end up with a

narrative that is considerably more interesting than the one given in a

simplified campfire song.

Bezimyackta,

or "the Girl with No Name", always fascinated me. As is true for many defiant Danubian children, I remember several times going out into the forest

and looking for her, and receiving the switch for my efforts. As an

adult, I pursued plenty of "serious" historical research endeavors, but

in the back of my mind I always wanted to find the truth about the

Girl-with-No-Name. Whenever I looked at church records and personal

diaries for other projects, I always hoped to find some reference to

her.

Bezimyackta,

or "the Girl with No Name", always fascinated me. As is true for many defiant Danubian children, I remember several times going out into the forest

and looking for her, and receiving the switch for my efforts. As an

adult, I pursued plenty of "serious" historical research endeavors, but

in the back of my mind I always wanted to find the truth about the

Girl-with-No-Name. Whenever I looked at church records and personal

diaries for other projects, I always hoped to find some reference to

her.

My search narrowed when I read the diaries of a city councilman written

during the years immediately before plague struck down Rika

Heckt-nemat's population. One paragraph that fascinated me focused on

the punishment of a peasant girl called Danka Siluckt in the early

summer of 1750. He described her as unusually pretty for a peasant,

mentioned that she worked for him, and added that she was sentenced to

the pillory for stealing apples. She was then either expelled from the

town and fled, or thrown into the Rika Chorna by the city guards to

drown. The councilman complained that the mystery of the girl's

disappearance kept him up at night and troubled his conscience.

An account from the town priest for the same time period corroborated

the councilman's diary entry. The clergyman added that Danka Siluckt was

viciously mistreated by the townsfolk, especially the women, while she

was restrained on the pillory and that it was a shame to see such a

pretty girl treated in such a harsh manner. Surly the Lord-Creator would

punish the city for such an immoral act. Interestingly, the priest also

seemed unsure whether Danka Siluckt drowned in the Rika Chorna river or

somehow managed to escape the city.

So, with the vital assistance of two colleagues and three graduate students, I pursued that lead, suspecting that

"the Girl-with-No-Name" had

started out as the peasant Danka Siluckt. We followed clues around our

country, establishing a time-line of her travels and the events of her

life. The search was not easy, because Danka was forced to assume

different identities during her travels, but I am confident our team of

researchers accounted

for all of her ten years of wandering.

Our research took us to the Seminary in Starivktaki Moskt, the University

in Sebernekt Ris, the Vice-Duke's compound in eastern Danubia, and the

site of the True Believers' Convent in Novo Sokukt Tok, just to name a

few places we visited. We took it for granted Danka was in Danubikt Moskt

during the Great Fire of 1755, and found numerous references to a

concubine called "Sister Silvitya" in the diaries of the Grand Duke's

advisors, castle matrons, and song-writers. The most important clues we

found for that period of her life were in the memoirs of Mayor Alexandrekt Bulashckt, the founder of the southern town of

Malenkta-Gordnackta, in which he described his escape from the Great

Fire with his family and a woman who had been one of the Grand Duke's

mistresses.

My companions and I are also convinced we know where Danka Siluckt ended up, after having

read the diaries of the Orsktackt family, which they so graciously

shared with us. During his later years, the estate-owner kept a journal

of his city's progress and politics, while his second wife, Vesna

Roguskt-Orsktacktna, wrote extensively about the farm and the growing

Orsktackt family. She also wrote some lines about what Rika Heckt-nemat

was like before the plague, and other comments about various places she

had seen while traveling around the Duchy. Those entries convinced us,

more than anything else we researched, that Danka Siluckt, "Sister

Silvitya", Vesna Roguskt-Orsktacktna, and several unnamed women who

briefly appeared in other towns, were all the same person, who ended up

being known as the "Girl-with-No-Name".

So, years ago I started looking for Bezimyackta and, with the

help of my research team, I found

her. Danka Siluckt's story inspired us more than we can put into words.

She was not a tragic figure at all, but instead an incredible young

woman who overcame tremendous odds in a Duchy that was much harsher than

the comfortable country we live in today.

As I traced her footsteps, I felt I got to know Danka. She is part of me,

as she is part of everyone who is a citizen of Danubia. And, as best as I

could reconstruct it, this is her story.

Chapter 1

----------

Note01:

"

Bezimyackta

" is a

combination of the following words: Bez (without), imyackt (name), and

the ending "a" which identifies the subject as female. The literal

translation of "Bezimyackta" from Danubian to English would be: "She who

is without a name". The name "Bezimyackta" does not directly indicate

Danka was young, just that she was female.

"The Girl With No Name" English translation of "Bezimyackta" may not be

literal, but it most accurately describes the context of the stories

based on Danka's life and how Danubians remember her. The popular lore

describing her travels always portrayed "Bezimyackta" as being the age

of a young marriageable woman at the height of her beauty. During the

late eighteenth century, women typically married when they were 16-18

years old. Peasant women tended to marry about a year earlier, when they

were 15-16.

- Maritza Ortskt-Dukovna -