“Well, hello!” said Wahata. “I’m glad you made it. And so promptly.” She beckoned Ana and Binta sit in the chairs opposite her in the small rundown café at which their rendezvous had been arranged. “You must have left Blad very early this morning!”

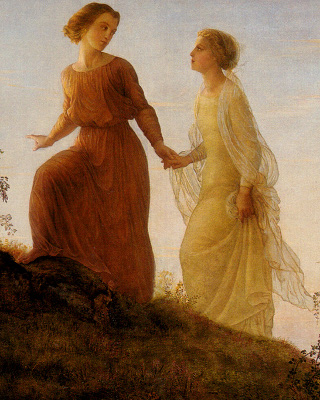

Ana yawned. Yes, it had been, but after a restless night in which neither she nor Binta got any sleep at all. This sleeplessness was partly to do with their forebodings for the day ahead, but more to do with the exertions of the two lovers’ reconciliation. They had got up extremely early, just as the first few rays of dawn sunshine streamed through the gaps between Blad’s tall office blocks, and humped their heavy suitcases down the steps to the ground floor, dreading that they should disturb anyone. Then into the city streets, heading across town towards the nearest railway station. As suggested, they bought tickets to a destination beyond that of the small border town of Bab , and sat separately in the train as it pulled off. Kerhala had warned them that secret police were much more widespread in Alif than Ana might imagine. Any unusual activity could attract very unwelcome attention - a category into which their early morning departure easily fell. The two women didn’t dare sit near each other until the train was well on its way and more people had embarked.

The journey took several hours, through barren plains bordered by mountains, past fields of peasants driving their donkeys and cattle, through small dusty towns and for nearly an hour along the length of a broad river on which boats were sailing in the bright light of the morning sun. The two girls were captivated by the vista, Binta especially. As she so often reminded Ana, not only had she never travelled such a long distance by train before, she had never seen any part of the world that was neither Jebel nor Blad.

“It’s so beautiful!” she sighed. “And I’ll probably never see these places ever again.”

Bab was one of the least prepossessing railway stations at which they’d stopped. Nobody else got off the train when they did, dragging their heavy baggage down the great drop onto the platform and across the railway lines to the main platform. A guard blew a whistle and the diesel locomotive thundered off carrying its relative security away from them. The station was dusty and badly maintained. The metal signs were rusting and broken. A few goats were grazing by the side of the tracks, and stared warily at the two fugitives as they struggled out of the station and onto the dusty dirt track outside. This was certainly no tourist destination.

The Safari Café was probably the only café in the whole village, and scarcely a very busy one. Two old men sat outside smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee, and the waiter barely seemed to notice them as they struggled in with their luggage past the gas bottles and freezer cabinet by the doorway, but Ana knew for sure that they had come to the right place when they saw Wahata sitting inside in the shade by a wooden bench wearing culottes and a striped tee-shirt nursing a half empty glass of black coffee.

“This is a pretty godforsaken village I’m sure you’ll agree,” said Wahata when the waiter had served Binta and Ana with two welcome but unpleasant tasting glasses of coffee. “Not really what anyone would choose as their last sight of Alif, but it suits our purposes. It’s less than ten miles from the Agdal-Alif border, and we can trust the villagers to be sympathetic. A few generations ago, Bab was a village in Agdal which along with the rest of the Safari district was conquered by Alif in one of those frequent wars which used to bedevil our two countries. People even now resent Alif occupation and the way they have been forced to drop their traditional customs for those of the invaders. I can talk to you quite freely here, and tell you all the things you need to know before I drop you off at the border. You’re probably asking yourselves though why we’ve arranged for you to leave the country at this particular point.”

“Well, yes,” admitted Ana whose conversation with Binta had been about little else when they realised how very desolate the village of Bab was. “And it’s still quite a long way from the border.”

“There’s a bus which comes to the border once a day. We shall time our arrival at the border to coincide with it to minimise suspicion. It would be too dangerous however for you to actually travel by it. It’s regularly searched by police and, at the very least, questions would be asked as to why you should be going to Agdal. The questioning is rarely subtle and it would be very disconcerting for you - particularly for Binta who has only just come out of the Brothel. It’s possible that the cost of them allowing you to continue on your way would be to provide sexual services for the police, and there’s no guarantee that they would be true to their word. You would certainly be expected to pay quite a substantial sum of money as a bribe. That would be the least you could expect without an Agdal passport. Agdal citizens do not expect or get that kind of treatment, though it’s almost routine for Alif nationals, particularly those without passports of any kind.”

Wahata paused, and leaned over to rummage in a large handbag she had by her side. She pulled out two green plastic booklets which she passed over to Binta and Ana. “With these, however, you should be a lot more secure, although we still have the odd complaint from our own citizens of very uncivilised behaviour from your minor officials.”

Ana looked at the booklet. It was her first sight of a passport, and it came as rather a surprise that such a very important document should look so ordinary. She was disconcerted to find that it was already creased and worn, with several visas already stamped inside, but there, on the opening page, was her photograph and the name Aghba Mustafubal printed underneath. Binta’s passport was in a similar state and the name inside was Harama Asine. Ana flicked through the pages, feeling a little disappointed. “Why are they both in such a bad state?”

“Common sense, I’m afraid. Passports in pristine condition would attract attention. Someone would be bound to suspect that they were forgeries. It’s not unknown, you see. We have deliberately distressed them and given them expiry dates which are really not far into the future. We have also faked an entry visa into the country, because that will be the first thing that the border guards will search for. Fortunately, Alif visas are not very sophisticated and extremely easy to forge. The names you’ve been given have been randomly selected but are more common in Agdal than they are in Alif. Your real names would also attract attention. We have to do everything possible to reduce the possibility of your being found out.”

“We’re very grateful,” said Binta. “You’ve gone to a lot of trouble on our behalf.”

“It’s not entirely for you alone. It is in our interest and that of the future success of the Amnesty from Oppression programme that you are not discovered. Agdal’s relations with Alif are always very fraught and President Marmeluke’s government isn’t at all averse to making high level complaints for every incidence of granting asylum to Alif nationals. The fewer such incidents known to your government the better for us. If they don’t find out now or in the future, the better it is for everyone, including any future petitioners. That’s one reason for moving so promptly on Binta’s release. The longer you tarried the more likelihood that someone somewhere might suspect something. What we hope is that people in your government will believe that you two have just disappeared: not an unknown phenomenon for people like you who have little to gain from being known as convicted lesbians. Our people are already laying tracks which will suggest just such an action.” Wahata turned to face Ana. “Have you phoned work yet to say that you aren’t coming in today?”

Ana shook her head. “No. I haven’t been near a telephone since we left Blad.”

“Well, you’d better call in now!” Wahata pulled a portable telephone out of her handbag and extended its aerial. “What we want you to say is that you have contracted ‘flu and that your doctor has advised that you take a week off work. We will send your office a forged doctor’s note which should allay suspicion. This will hopefully buy you a little time.”

“Why do you want to do that if we’re going to be in Agdal by this evening?” wondered Binta.

“It’s not for you we want to buy time, but for your friends and colleagues. They will be as mystified as anyone when you don’t turn up for work again, and with the benefit of extra time it is likely that when it is known that you have absconded from work plenty of other alternative theories and hypotheses will have propagated which will muddy the waters a little bit and lessen the chances of the correct solution being arrived at. I can’t emphasise too much how much risk your friends may already be in if the slightest suspicion reaches the appropriate authorities.”

With her heart thumping painfully and a glaucous mass lodged in her throat, Ana carefully punched in the digits of her work telephone number. She started with surprise when the bleeps of the automatic dialling resolved themselves into a piercing whistle, but then she realised she’d not prefixed it with the dialling code for Blad. She reset the receiver, punched in the longer code and waited with trepidation as the phone at the other end rang and rang. It was not at all welcome to her when the voice that barked angrily down to her was unmistakably the Director’s.

“Hello. Who is it?”

“It’s me, Ana.”

“You! What are you ringing in for? Why aren’t you here, you bitch? Why didn’t you ring in earlier? How do you expect the office to run without you?”

“I’m ill. I’ve got ‘flu.”

“‘Flu, my foot, you slut! You should be here. Come in this minute.”

“I’ve got a doctor’s note. He says I’ve got to stay off work for at least a week...”

“A week? You lazy bitch! You better send that note in, m’dear. Bit of a coincidence, isn’t it, you getting ‘flu on the day after your dyke girlfriend leaves the Brothel. You’re not with her, are you? Dyking about together?”

“I don’t know where Binta is. I ... er ... I didn’t even know she was due out.”

“Lying dyke!” snorted the Director. “That means I’ll have to hire a temp. Didn’t give me much warning, did you bitch? You seemed all right yesterday.”

“It came on very suddenly. I feel very ill.”

“Huh! Well, I suppose you just haven’t got the stamina, have you m’dear? I’ll have to cancel the clients I arranged for you this week. They’re going to be damned disappointed. Get well soon, and I won’t have any sympathy for you if you’re off one day longer than the doctor’s note says. Stupid bitch dyke!”

With that there was a sudden click as the Director put his receiver down. Ana gently lowered the portable phone, and stared at Binta and Wahata with a face drained of all colour.

“Your former boss doesn’t sound like a very pleasant man,” commented Wahata mildly.

“He’s really horrible!” Binta exclaimed. “He’s always seducing the girls at the Brothel and treats them really badly. You wouldn’t believe some of the obscene things he’s had poor Ana submit to!”

“I’ve been in this business just long enough to believe anything, I’m afraid. Alif is not a country famous for the kindness that its men treat its women.” Wahata stretched a hand over to grasp Ana’s which was still gripping the phone and staring at it blankly. “You handled that very well, Ana. Your boss clearly suspects that there is a connection between your absence and Binta’s release. We shall have to watch your flat carefully to see whether he sends anyone to investigate. It’s likely that what he’ll be expecting is that Binta and you will be there together, so not finding either of you there may rather shock him. As long as no connection is made between your disappearance and the Republic of Agdal then no unfortunate conclusions may be drawn.” Wahata turned to face Binta. “Although you are free from the Brothel, are there any appointments which you are due to make with anyone? Perhaps on the Brothel’s post-employment rehabilitation programme?”

Binta shook her head. “No. Not at all. It’s just a way they have of trying to persuade people like me to continue working for the Brothel after we’ve been released. There are no jobs in Alif, except in places like the State Brothel, and I want nothing at all to do with it in future.”

Wahata nodded. “Your uncooperative behaviour over the last few years will have made such reasoning totally plausible. So, the authorities presumably have no way of tracing you. That’s all for the good. Unless something very untoward happens in the next few hours, you have both seen and heard the very last of the Brothel, and I dare say you must be delighted if that’s the case.”

Ana’s phone call to the Director still shook her. She eased her grip on the phone and handed it back to Wahata who carefully dropped it into her handbag. “He’s such a horrible man!”

Wahata nodded sympathetically. “Many men in Alif are like him. A country like yours seems to encourage male chauvinism. Not just in Brothels, of course. In every walk of life. In hotels, offices, factories, everywhere where women work. Women are very much second class citizens here, derided when they are successful, despised when they’re not. It’s not the worst country in the world in that respect, but it’s clearly not the best. You’ll be much happier in Agdal, I’m sure, where there are laws to protect women from the worst excesses of male behaviour, though I’d be lying if I said there weren’t far too many instances of male harassment and chauvinism in Agdal too. Alif is not a country which seems likely to improve the lot of its women in the near future and while men like your Brothel Director remain in positions of power and influence it’s unlikely to happen very soon at all.”

“Are there other ways in which Agdal is better than Alif?” wondered Binta.

“It’s more difficult to think of many ways in which Alif is at all better than Agdal. But President Marmeluke’s government would not be in power at all if it didn’t govern with the consensus of at least a sizeable minority of its citizens. I’m not saying that it is legitimate in the sense that it actually does win those fabulous majorities in your national elections that it so consistently claims. No party in Agdal has ever gained the massive electoral support your government boasts. What I’m saying is that there are enough people in your country who genuinely believe in the policies of your President Marmeluke to keep him in power until another would-be dictator comes along and by treachery or deceit manages to oust him from power and become president himself. It’s unlikely though that any change of government in this way would make much difference to the policies your government pursues, whoever the actual individuals composing it are.”

“But you managed to change your government in Agdal,” objected Binta. “Surely the same could happen in Alif.”

“Perhaps. Perhaps. But at great cost, I can tell you! It took at least a decade of chaos, civil war and invasion until Agdal evolved into the nation it is now. Many thousands of people died in the process and it didn’t always seem inevitable that a liberal or enlightened regime would take power. I’m not sure I would gladly wish that kind of penalty on the people of Alif in their desire to attain better rights and economic prosperity.”

Wahata signalled to the waiter who had been standing out of earshot in the entrance to the café. He wandered towards them, as Wahata stood up and paid for the coffees. “Right!” she announced to Binta and Ana. “We’d better get going.”

The three of them strode into the dusty unmetalled road running through Bab, lined by sandy coloured buildings, on whose flat roofs were washing lines and the occasional television aerial. Wahata led them down the road to an area of dusty ground where a car waited amongst the odd blown page of newspaper and a sleeping dog. Ana was surprised to see that the car was really not the grand Embassy limousine she’d expected, but, while Wahata was turning her key in the car door to release all the door locks, she reasoned that this too was not to attract unwelcome attention. It was quite modest, not at all new and the number plates were familiar as belonging to Blad. The three of them entered the car, Binta sitting in the front next to Wahata.

“We’ll be arriving at the border rather early,” Wahata announced. “The bus isn’t due to arrive for at least an hour, but I think it’s rather better to be early than late.” She turned the key in the ignition and steered the car onto the road, bumping uncomfortably over the uneven ground. Wahata drove carefully and slowly, avoiding the potholes and hens scattered about the road.

“You may wonder why we’ve selected this particularly border post for you to leave,” Wahata said. “There are after all many such border posts, and most are a great deal more salubrious. For instance, one could have left the country by ‘plane, bus or train. All much more convenient than this. But our objective is to minimise risk as much as possible. The passport control and customs here are much more lax than most others in Alif. They would be less likely to pick up on the fact that you don’t have Agdal dialects and are dressing rather more conservatively than Agdal women would. They would also be less likely to be amongst the first border posts notified if your descriptions were circulated should anyone suspect you were trying to leave.”

“Surely, no one knows that we’re here,” Ana remarked from behind Wahata’s head.

“Nobody knows, but they may have their suspicions. Who knows whether one of your colleagues at the Brothel has discovered about your escape, by whatever means I couldn’t say, and has broadcast it to the authorities. Your boss has made the connection between Ana’s day off sick and Binta’s release. Although that connection may be useful later on in explaining your abrupt departure from the Brothel, it may be that his suspicions may be further aroused. Events like these have been known to happen, and in cases under my care as well.”

“What happened in those cases?” Binta asked. “How did they find out? What did they do?”

“I don’t know the answer to your questions at all, but I remember clearly one case I was supervising. Through a different crossing point to this. In fact, it was by sea. We do try to vary our selection as much as possible within the slim choice of relatively lax crossings. Like today, I escorted the man and his wife, who were being persecuted for their political activities, to the crossing point, as far as I could go - the actual crossing has to be done without any assistance from me I’m afraid. I watched them walk to the border patrol, and spent several anxious moments from a vantage point in the harbour waiting for them to pass through and embark on the boat. I waited and I waited, and still there was no sign of them. Eventually, I abandoned the wait and drove back to the Embassy. The first I knew about them for sure was that neither of them ever arrived in Agdal. The next I heard was in a report in one of your national newspapers. They were one of many in a list of people arrested for alleged alcohol smuggling and corruption of minors. What happened to them after that I don’t know, but I can only fear the worst.”

Wahata continued driving along the uneven roads, past derelict farm houses and fields in which women farmworkers wearing scarves over their hair were bent double over the crops they were working on. In the middle distance, some splendid mountains towered above, which Wahata identified as being on the Agdal side of the border. The only other traffic they passed were carts pulled by oxen or mules, and a small open-topped van in which several women were sitting, watching the fields as they went by. Among them was a thin teenage girl with most of her front teeth missing who smiled broadly at them as they passed. Both Binta and Ana were captivated by the view, while Wahata drove doggedly on, occasionally cursing the state of the roads. “I don’t think they’ve been maintained since this was Agdal territory!” she remarked bitterly at one stage.

Eventually, Wahata stopped the car by a derelict farmhouse, and parked it out of sight of the road. She pointed at a single bus shelter just by the road which had none of its windows and very little of its roof left intact. A few people were gathered there disconsolately between their bags and suitcases. “That’s where I suggest you wait until the bus arrives. Those other people have come through the border from the Agdal side, and are no doubt waiting for the bus to take them deeper into Alif. There are very few buses which can travel through the border, and the bus which comes here does a round trip. This is where it drops off those heading for Agdal, and picks up those who’ve just arrived. For the moment you will be masquerading as people heading into Alif. Avoid talking to anyone and if you have to, be as noncommittal as possible about where you come from and what you’ve been doing on your supposed holiday in Agdal. It’s quite likely that the only people who’d be interested in you are not people with your best interests at heart. It’s possible that there may be a secret policeman surveying the border for contraband and very likely to be scouting for his own slice of the pre-sale proceeds of alcohol or drug smuggling. It may be that you’ll be approached by smugglers who would try to tempt you into a profitable sideline. Guard your bags well. If it’s thought that you’re going into Alif, someone may slip some contraband into them to protect themselves from being caught on the bus by the police. Don’t even look at people. Do you understand? It’s very important that you do.”

Ana and Binta nodded. “Every stage of this journey seems fraught,” Binta remarked bitterly.

“It is, I’m afraid. You can’t actually see the border patrol from here, and you won’t be able to see it from the bus stop. It’s about a hundred metres further on, just over the slight ridge. But you can see the border.” Wahata indicated a long barbed wire fence occasionally topped by tall watch towers. The dead body of a goat was lying by one point. Beyond the barbed wire was desolate countryside much like that on the Alif side of the border, and then a second row of barbed wire a twenty or so metres beyond. There was no other feature in the whole landscape.

“Be prepared to hand over all the money you have. It’s actually illegal to export money from the country, but I don’t believe there’s any harm in having some Alif money on you. The patrols are accustomed to the idea of Agdal visitors not spending all their money, and they’ll be quite happy to relieve you of it. It’ll actually make the crossing easier for you if they get something out of you, and it is more typical of Agdal carelessness with money than Alif parsimony. However, you’ll need these.”

Wahata handed over a few worn change receipts from Alif banks. Ana examined them. There was an awful lot of money that had been changed. How could anyone ever have spent so much money?

“And here’s some Agdal currency.”

These notes were similarly worn and unlike Alif notes did not feature a portrait of the head of state. Instead there were pictures of historical figures Ana had never heard of and strange mythical beasts which were the emblems of Agdal.

“You’ve been on holiday in Alif for two weeks. If anyone asks you at the border, you found everything in Alif very cheap, but the hotels were dreadful. Complain about how you’ve been perpetually harassed by men during your stay, but say nothing which could be interpreted as criticism of the government, and especially not of President Marmeluke.”

Wahata opened the car door, and Binta and Ana followed Wahata as she got out of the car, pulling their bags out of the boot.

“Now, make your way to the bus stop. Keep as much out of sight of the road as you can. Wait till the bus arrives and join the other people as they head towards the border. On no account be among the first to arrive, and try not to be the very last. Somewhere in the last five or six would be best. Answer all questions briefly and with no ambiguity. Surrender some if not all of your Alif money if asked, but bear in mind that there is no consistency to the questions that will be asked or the demands that will be made. Accept that your luggage will be searched, ostensibly for alcohol and drugs (though why anyone would wish to smuggle them out of Alif I really don’t know!), and that items will almost certainly be confiscated. Don’t appear too resigned to their loss, but don’t make too much fuss about it. Remember your new names and particularly your homes. Remember that the last hotel you stayed in was the Hotel Marmeluke in Blad.”

“What do we do when we get to Agdal?” Binta asked.

“I was just about to get to that. Go to the nearby town of Alan and book a room at the Hotel Liberty. You will soon be met by officials from Agdal who will guide you through your first few days in the country. They’ll organise a flat for you to stay - probably in one of the cities - and help you find a job. There are plenty of jobs in Agdal’s cities if you don’t mind working in a fairly menial capacity at first.”

Wahata scratched her face in the hot midday sun. “Well, I think that’s everything. Remember everything I’ve told you, and don’t even speak to each other until you get through the border. Anything you say even to each other could arouse suspicion. I hope it all goes well, and that if I ever see you again it’ll be on the Agdal side of the border. Best of luck!”

With that, Wahata turned to each of them, and gently hugged and kissed them in turn on the cheek. She smiled bravely, and then turned round to her car. She got inside, and pointedly turned her face away from them. The last words she said before the two lovers wandered along to the bus shelter weighed down by the heat of the sun and the bulk of their bags were: “Don’t wave to me when you leave. It might attract unwelcome attention. Good luck again!”